Imagine a roll of celluloid stretched out the length of a football field, plus a couple of end zones. Now imagine a film 20 times that long. Now multiply that by 15. The result is a strip of film 400 football fields long - 120,000 feet, or nearly 23 miles of celluloid - which is close to the amount of film processed by NFL Films on any given weekend during football season.

Imagine a roll of celluloid stretched out the length of a football field, plus a couple of end zones. Now imagine a film 20 times that long. Now multiply that by 15. The result is a strip of film 400 football fields long - 120,000 feet, or nearly 23 miles of celluloid - which is close to the amount of film processed by NFL Films on any given weekend during football season.

Now imagine a glitch that imperils this entire film-developing process, jeopardizing the delivery of Sunday's action footage to fans throughout the world. It gives new meaning to the term "disaster film," doesn't it?

Well, that's what NFL Films pays Paul Delplace to worry about. As the company's laboratory engineer, Delplace is responsible for maintaining the film-processing equipment at the outfit's Mt. Laurel, NJ, laboratory, and ensuring that it's up and running when the tide of unprocessed film from 15 football games comes flooding in on Sunday afternoons during the season.

Delplace was elated when he recently discovered a product that would help him avert the dreaded specter of downtime while the world awaited the weekend's football highlights. The product, PLV 2100, manufactured by Pelseal Technologies, LLC, of Newtown, PA, is the same liquid sealant NASA uses on its space shuttles.

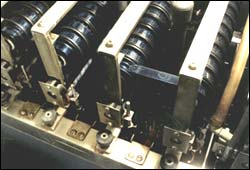

To process NFL film, the laboratory utilizes about 125 tanks. Color negative film, which accounts for most of the volume, is fed through a succession of 11 stainless-steel and titanium tanks - from pre-bath through developing, fixing, washing and stabilizing.

Although some of the processing chemicals are corrosive, a majority of them pose no threat to stainless steel. In principle, at least, says Delplace, "It's like filling your glass at home with water. It should stay there for thousands of years; it's not going to leak."

In 1999, however, the unthinkable happened. It was becoming evident that the fixer tank in the color-negative processing line, a vessel measuring 4 feet deep and 12 inches x 17 inches at the top, was leaking significantly. "I had no idea how big the problem was," recalls Delplace, "but it was bigger than normal. I suspected a weld let go or a seam might have opened up.

"After a lot of detective work, I finally concluded the leak was at the bottom of the tank. When I got down to one-and-a-half feet from the bottom, it was still leaking. I checked with as many lights as I could get into the tank, and crawled in as deep as I could go to check if I could see something, but it's almost impossible unless you have a crack that's real big. Yet liquid was running out of the tank like nobody's business. We lost three feet of chemical over one weekend.

"This particular machine is a son-of-the-gun in terms of removing the tank," he asserts. He explains that before the tank can be removed, the caps, assemblies and other structural components have to be removed; when everything is put back, it all has to be realigned. "It's a very big and time-consuming job," he notes. "It's like changing the spark plugs in your car by going through the trunk, cutting a hole in the firewall and working your way into the engine compartment. If I didn't have to take the tank out, I wasn't going to."

Delplace's first thought was to visit a marine-supply store to find an epoxy paint or coating used for protecting boats from salt water, but then he remembered Pelseal Technologies. Pelseal, located just across the Delaware River from NFL Films, specializes in the manufacture of products formulated from DuPont Dow Elastomers' Viton fluoroelastomer. Fluoroelastomer, a synthetic rubber, has been around for 40 years. For most of this time, it has been used primarily in molded or extruded products, such as O-rings and other rigid seals. Because of their ability to resist temperature extremes and corrosive liquids, fluoroelastomers are widely used in applications characterized by harsh environments, such as aircraft and automobile engines. Reasoning that such properties could be equally valuable in liquid products, Pelseal has focused on the marketing of fluoroelastomer adhesives, sealants and caulks.

Pelseal, located just across the Delaware River from NFL Films, specializes in the manufacture of products formulated from DuPont Dow Elastomers' Viton fluoroelastomer. Fluoroelastomer, a synthetic rubber, has been around for 40 years. For most of this time, it has been used primarily in molded or extruded products, such as O-rings and other rigid seals. Because of their ability to resist temperature extremes and corrosive liquids, fluoroelastomers are widely used in applications characterized by harsh environments, such as aircraft and automobile engines. Reasoning that such properties could be equally valuable in liquid products, Pelseal has focused on the marketing of fluoroelastomer adhesives, sealants and caulks.

Delplace was already familiar with Pelseal's PLV 2040, an aerosol fluoroelastomer coating which NFL Films had used before to seal lightly pitted steel surfaces. "I got in touch with (Pelseal President) Bill Ross, Jr., told him the situation and asked, 'What else have you got?'" remembers Delplace. "Ross suggested PLV 2100, which had a heavier viscosity than the aerosol spray. He sent over a couple of samples and told me how to use it."

Following Ross's instructions, Delplace emptied the remaining chemicals from the fixer tank, washed it thoroughly to remove all residue of the chemical, roughed up the tank bottom and 12 inches of the side walls with 180-grit sandpaper, and cleaned the surface with alcohol.

To reach and coat the almost inaccessible bottom and sides of the tank, Delplace improvised with an angled, 30-inch utility brush, which he found by chance at a home-improvement store. He added a 5-foot extension to the brush handle. The extra length and the angled end enabled him to apply coating to the previously unreachable bottom, sides and corners of the tank.

Ross suggested three coats be applied in adequate intervals to avert blistering. Delplace decided to take no chances. "I let it go (between coats) for days rather than hours, and I got no blistering at all," he reports.

The final coat was applied on a Friday morning. The following Monday, Delplace filled the tank to overflow level with fixer "and let it stay that way for several days. After three and a half days, the level of fixer was virtually unchanged (except for normal evaporation), and I knew the coating had done the trick.

"We put the two assemblies (the rollers through which the film is threaded) back in the tank," he concludes, "and we've been running the machine every single day since then with no leaks. If that hadn't worked, the next step would have been to take apart the entire machine. If we'd had to replace the tank, it would have cost in the neighborhood of $7,000 to $10,000, apart from labor and downtime. Had it happened during the season, we'd have lost several weeks of production, or it would have forced us into overtime expenses."

Within the next year, NFL Films expects to break ground for construction of a new, 200,000-square-foot facility on a nearby 26-acre site. In preparation for the move, which will quadruple the company's working area, NFL Films management plans to look at alternative equipment designs with the hope of preventing future leaks.

"I asked Bill Ross, 'What happens if we get another leak in the meantime?'" Delplace muses. "(He said), 'No problem. We have another product with a heavier viscosity.'"

Used by permission of American Cinematographer. Copyright © 2000

Latest News

![]() Commercial Boiler Corrosion Solved with Pelseal Viton™ Caulk (read)

Commercial Boiler Corrosion Solved with Pelseal Viton™ Caulk (read)

Flanges leaking acid? You need FLANGE PELSEAL, our liquid Viton caulk. See the independent test results in our new photo brochure. (read)

Pelseal Technologies Featured In SULFURIC ACID TODAY Magazine (read)

Pelseal Technologies New PLV2020 Aerosol Coating Features the Properties of Viton™ Fluoroelastomer in a Convenient, 12 oz. Spray Can (read)

3161 State Road, Ste. G

Bensalem, PA 19020

Phone: 215-245-0581

Fax: 215-245-7606

sales@pelseal.com

Disclaimer: Information and suggestions supplied by Pelseal® Technologies, LLC ("Pelseal"), whether in published literature or otherwise, including samples, are based on technical data that Pelseal believes to be reliable. Such information and suggestions are supplied without charge and their use, and the use of Pelseal's products, are beyond Pelseal's control. Pelseal's products, information and suggestions are intended for use by persons having technical skill and know-how in the industry. Such persons are responsible, at their sole discretion and risk, to satisfy themselves regarding the suitability of Pelseal's products, information and suggestions for their particular use and circumstances. Any handling precaution information is given with the understanding that those using it will satisfy themselves that their particular use conditions present no health or safety hazards. NOT FOR RESIDENTIAL USE.